Confirmation Bias: How Your Beliefs Build (and Wreck) Your Reality

- Natasha Bussey

- Oct 29, 2025

- 8 min read

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”― Carl G. Jung

A Therapist’s Reflection: You’re Not Neutral, You’re Editing Reality

In therapy, people often tell me, “I just want to see things clearly.” And I have to gently say, “You can’t. None of us can. Your brain is already editing.” I also often hear clients say, “The objective reality is…” Well, there isn’t one. Any reality, under the eye of the observer, becomes a subjective perception of what goes on.

What you believe, you start looking for. What you look for, you start seeing. What you keep seeing becomes “evidence.” Then you say, “See? I was right.”

That loop is called confirmation bias. And it quietly runs your relationships, your self-esteem, your anxiety, your career, and—yes—your healing.

I’ve watched clients walk into dating situations convinced “people always leave,” then subconsciously test their partners until the partners back away. I’ve watched brilliant women believe “I’m not leadership material,” then avoid opportunities that would have proven that belief wrong—and call that avoidance “being realistic.” I’ve watched trauma survivors believe “I’m not safe,” then interpret every neutral expression as a threat and live in permanent adrenaline.

Here’s the wild part: most of these beliefs weren’t born from truth. They were inherited—family messaging, culture, early hurt, survival strategy. They feel like “me.” They’re not always you.

Let’s talk about how your brain creates reality—and how to take some of that power back.

Confirmation Bias 101: Your Brain Likes Being Right, Not Being Accurate

Confirmation bias is the tendency to seek, notice, and remember information that supports what we already believe—and to ignore or downplay information that contradicts it [1]. It’s not a moral flaw. It’s a brain efficiency hack.

Classic research by Peter Wason showed that when people are asked to test a rule, most try to confirm it rather than disconfirm it [2]. In plain language: instead of asking “Could I be wrong?” we instinctively ask “How am I right?”

Neuroscience adds a layer of spice here. When we receive information that confirms our beliefs, reward circuitry in the brain activates; when we get disconfirming evidence, areas associated with cognitive conflict light up [3]. Being right literally feels safer and more rewarding than being accurate.

So your brain is not an objective detective. It’s a defense attorney with a full-time job: protect the story.

Invisible Gorilla, Red Cars, and Why You Miss What Doesn’t Fit

If you’ve never seen the “invisible gorilla” experiment—pause here and watch it while paying attention to only the basketball being passed among players:

…Okay. Now that you’ve either watched it or scrolled past thinking you’re above being tricked (you’re not, none of us are), here’s what just happened.

In the original study, participants watched people in white shirts and black shirts pass basketballs and were told to count the passes made by one team [4]. Half of participants did not notice that a person in a full-body gorilla suit walked into the scene, beat their chest, and walked out.

Half. Missed. A gorilla.

Why? Selective attention. When your brain is instructed to look for X, it will literally filter out Y—even when Y is a gorilla waving at your face.

Same thing happens with the “red car phenomenon.” You decide you want a red car and suddenly you see that exact make and model everywhere. The cars were always there. Your attention just got tuned.

Psychologists call this attentional bias—we attend to what we expect and deem relevant [5].

Now apply that to core beliefs like:

“People can’t be trusted.”

“I’m not worthy.”

“Everything always goes wrong for me.”

“No one understands me.”

If you’re scanning for betrayal, you will notice every micro-disappointment. If you’re scanning for rejection, neutral feedback will feel brutal. If you’re scanning for danger, safety won’t even register. You will literally miss the gorilla named “You’re actually okay.”

Self-Fulfilling Prophecy: Belief → Behavior → Outcome → ‘Proof’

This is where it gets existential.

Sociologist Robert Merton called it the self-fulfilling prophecy: a belief that becomes true because it changes the way you act [6]. Psychologically, here’s how that plays out:

You believe a story. (“People leave.”)

You behave in ways that protect you from that story. (You don’t get too close, you test them, you hold back parts of yourself.)

The other person eventually feels shut out, criticized, or like you don’t trust them. They pull away.

You say, “See? People leave.”

That loop also shows up internally. Research on self-concept and performance shows that expecting failure reduces effort, help-seeking, and persistence—and those things, surprise, increase failure [7]. You didn’t “just fail.” You partially created the conditions in which thriving was not allowed.

It’s not that you’re manifesting outcomes with “energy.”You’re enacting outcomes with behavior that aligns with your core belief.

Where Beliefs Come From (Spoiler: A Lot of Them Aren’t Yours)

When I ask clients, “Whose voice is that?” they usually go quiet.

A lot of what we call “my beliefs” are actually adaptations. They’re internalized rules we built to survive pain.

Examples:

“If I don’t need anything, I won’t be disappointed.” (Child of emotional neglect.)

“If I anticipate criticism first, it won’t hurt as much.” (Child of harsh perfectionistic parenting.)

“If I assume danger, I’ll never be caught off guard again.” (Trauma survivor.)

These are not random thoughts. They are nervous system policies. They once kept you safe.

But here’s the complication: beliefs that protect you in one environment can imprison you in another. A client who learned “Being vulnerable gets you laughed at” at 12 may, at 32, desperately want intimacy—but the system still runs the 12-year-old’s code. Neuroscience on trauma and memory supports this: fear conditioning can generalize far beyond the original context, leading to chronic hypervigilance and misinterpretation of neutral cues as threat [8].

So before you judge yourself for “thinking negatively,” try respecting the brilliance of your survival. Then ask, with love, “Is this belief still serving me now?”

Cognitive Rigidity vs. Cognitive Flexibility: Why Some Brains Can Update and Others Get Stuck

Psychologically healthy people aren’t “positive thinkers.” They’re flexible thinkers.

Cognitive flexibility—the ability to update beliefs in response to new information—is associated with better emotional regulation, resilience, and interpersonal functioning [9].

Cognitive rigidity—clinging to a belief even when reality disagrees—is associated with anxiety, depression, and relationship strain [10].

And here’s the hopeful part: flexibility is trainable! Therapies like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) work, in large part, by helping you notice thoughts as thoughts—not as absolute truth—and then experiment with new behaviors anyway [11][12]. When behavior changes first, the brain is forced to update its model. Action becomes evidence.

How to Start Rewriting Your Reality (Without Gaslighting Yourself)

Let’s be clear: this is not “just think positive.” Fake positivity is denial, and your nervous system is too smart for that. This is about practicing evidence-based mental flexibility.

Here are practical tools to start interrupting confirmation bias and loosening the grip of old beliefs:

1. The Disconfirming Evidence Drill

Write down one painful belief (“I’m not lovable,” “People always leave,” “I always ruin things”). Then list 3 moments from the last 12 months that do NOT support it. Small things count. Someone checked on you. Someone stayed. Something went well.

Why it works: We naturally attend to confirmatory data and under-encode disconfirming data [1][2]. This drill forces retrieval of contradictory memory, strengthening more balanced self-narratives.

2. Behavioral Experimenting

Instead of arguing with your belief, run an experiment. Example: “No one supports me” → ask one specific person for one specific kind of support. Observe what actually happens.

Why it works: CBT research shows that behavioral experiments are one of the most effective ways to update core beliefs, because they generate live data instead of theoretical debate [11].

3. State the Fear, Not the Story

Instead of “You don’t care about me,” try “I’m scared I don’t matter to you.”

Why it works: This shifts from accusation (which triggers defensiveness in others) to vulnerability (which invites connection). Studies of attachment communication show that this style improves responsiveness and closeness in relationships [13].

4. Future-Tense Audit

Notice how often you predict the future as fact: “This meeting is going to be a disaster,” “They’re going to judge me,” “I’m going to mess this up.” Add one phrase: “…and I don’t know that yet.”

Why it works: Catastrophic prediction is a core driver of anxiety. Introducing uncertainty language has been shown to reduce anticipatory threat arousal and increase tolerance for not knowing [14].

5. Curiosity Reframe

Ask, “What else might be true?” or “What would I notice if I were wrong?”

Why it works: Curiosity reduces defensive processing and opens prefrontal networks involved in cognitive flexibility [9]. You’re not forcing yourself to believe the opposite. You’re giving your mind permission to consider it.

Changing Your Destiny by Changing Your Beliefs (Yes, Literally)

Here’s the part that still gives me chills.

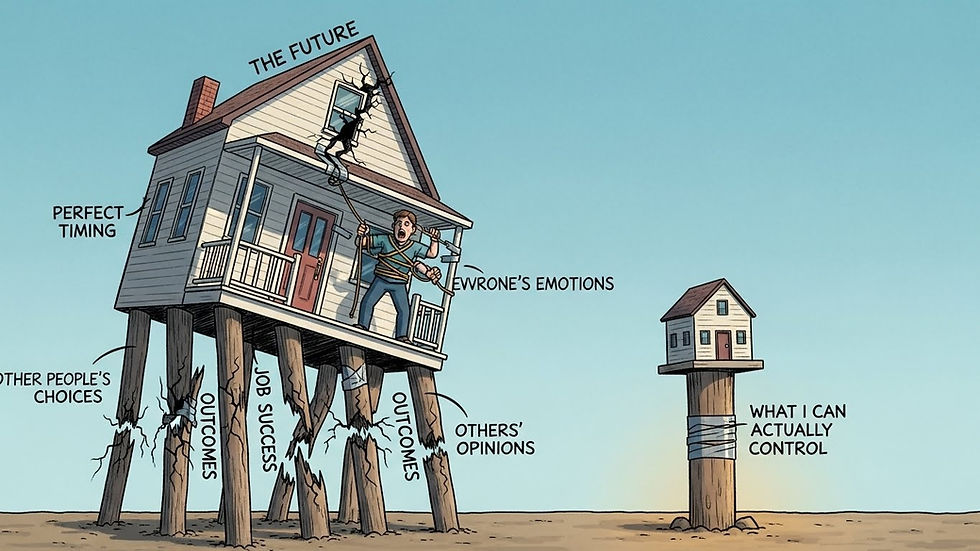

Your beliefs quietly script your behavior, which quietly sculpts your outcomes, which quietly becomes your life. That means you are not just living in reality—you are participating in building it.

If you believe “I’m allowed to take up space,” you will speak more. You will apply. You will ask. You will set boundaries. You will leave. You will stay. You will negotiate. Over a year, that doesn’t just change your mood. It changes your career, your relationships, your mental health profile, your sense of self—all of it.

If you believe “I don’t matter,” you will under-ask, over-give, resent, collapse, isolate, and then cite the isolation as proof that you don’t matter. That is not destiny. That is a loop you are allowed to interrupt.

Here’s the invitation: Don’t just ask, “Is this belief true?” Ask, “What does this belief produce?” If the answer is “pain,” it’s not wisdom. It’s programming.

You’re allowed to rewrite it.

References

[1] Nickerson, R. S. (1998). Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology, 2(2), 175–220.

[2] Wason, P. C. (1960). On the failure to eliminate hypotheses in a conceptual task. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 12(3), 129–140.

[3] Sharot, T., Korn, C. W., & Dolan, R. J. (2011). How unrealistic optimism is maintained in the face of reality. Nature Neuroscience, 14(11), 1475–1479.

[4] Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: sustained inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28(9), 1059–1074.

[5] MacLeod, C., Mathews, A., & Tata, P. (1986). Attentional bias in emotional disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 95(1), 15–20.

[6] Merton, R. K. (1948). The self-fulfilling prophecy. Antioch Review, 8(2), 193–210.

[7] Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147.

[8] Rauch, S. L., Shin, L. M., & Phelps, E. A. (2006). Neurocircuitry models of posttraumatic stress disorder and extinction. Biological Psychiatry, 60(4), 376–382.

[9] Dennis, J. P., & Vander Wal, J. S. (2010). The cognitive flexibility inventory: Instrument development and estimates of reliability and validity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(3), 241–253.

[10] Fresco, D. M., et al. (2007). Cognitive rigidity and depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31(4), 419–436.

[11] Beck, A. T. (1976). Cognitive Therapy and the Emotional Disorders. International Universities Press.

[12] Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Guilford Press.

[13] Johnson, S. M. (2004). The Practice of Emotionally Focused Couple Therapy. Brunner-Routledge.

[14] Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O. M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. G. Heimberg et al. (Eds.), Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Guilford Press.

Comments