The Paradox of Healing: Why Developing Self-Compassion Is the Hardest—and Most Important—Work You’ll Ever Do

- Natasha Bussey

- Oct 24, 2025

- 11 min read

A Therapist’s Reflection: When Healing Feels Like a Bootcamp

After sitting with clients in the sacred trenches of healing, one truth keeps hitting me like a psychological plot twist: the people who make the deepest, most sustainable progress aren’t the ones who push themselves the hardest—they’re the ones who learn to treat themselves with compassion.

I used to watch clients approach therapy like a self-improvement bootcamp. They came determined to “fix” themselves, logging emotional reps as if healing were a contest of endurance. Many labeled themselves broken, weak, or behind schedule. Their drive was admirable—but their progress was glacial. They judged every setback as proof of failure. The more they demanded change, the more their inner worlds clenched in resistance.

Then I noticed something radical: the clients who made lasting progress were the ones who learned to stop performing and start befriending themselves. They stopped hustling to become whole and began allowing themselves to be whole. That’s when the real healing happened. It wasn’t until we began weaving self-compassion practices into our work that transformation started to take root. Clients who learned to soften toward themselves began rewiring their nervous systems for safety, not punishment—and therapy suddenly worked.

As Brené Brown shares in her TED Talk, The Power of Vulnerability, vulnerability isn’t weakness; it’s courage in motion. The same is true for self-compassion. It’s not weakness; it’s emotional strength wearing sweatpants. You can’t heal what you still resent.

The Science of Self-Compassion: Why It’s Not “Being Nice to Yourself”

If you’ve ever rolled your eyes at the idea of self-compassion, you’re not alone. For most people, the concept sounds suspiciously like self-indulgence—bubble baths and affirmations while the world burns. Let’s recalibrate. Underneath the warm fuzziness is hard neuroscience.

Dr. Kristin Neff, the pioneering researcher who defined self-compassion, describes it as treating yourself with the same warmth and understanding you’d offer a good friend who’s struggling [1]. It is “extending kindness to oneself in instances of perceived inadequacy, failure, or suffering.” Her framework has since been validated in hundreds of peer-reviewed studies. It consists of three interlocking components:

Self-Kindness vs. Self-Judgment – Speaking to yourself with gentleness instead of hostility.

Common Humanity vs. Isolation – Recognizing that struggle is part of being human, not proof of defectiveness, and remembering that everyone struggles.

Mindfulness vs. Over-Identification – Holding pain in balanced awareness rather than drowning in it, without exaggerating or suppressing it.

This isn’t just feel-good psychology—it’s biochemistry. When you’re self-critical, your brain lights up the amygdala (threat system), dumping cortisol into your bloodstream. Brain imaging research backs this up.

Longe et al. (2010) found that when people engage in self-reassurance instead of self-criticism, activity decreases in the brain’s threat system (amygdala, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex) and increases in the soothing system (insula, ventromedial prefrontal cortex). The result? Lower cortisol, higher oxytocin, and greater emotional regulation (Rockliff et al., 2008). Translation: compassion literally turns down the volume on your inner alarm system.

This shift is more than emotional—it’s physiological. Self-compassion rewires the nervous system to move from survival mode to growth mode. When you meet your pain with care, your brain interprets that as safety. Safety allows neuroplasticity. Neuroplasticity allows healing.

A meta-analysis of 79 studies found that people high in self-compassion had significantly lower levels of anxiety, depression, and stress [3]. For trauma survivors, self-compassion even mediates the link between early trauma and adult distress [4]. You can’t heal if your brain thinks you’re still under attack—and self-compassion tells it, You’re safe now.

In short: self-compassion is not a luxury or a mood—it’s a biological prerequisite for change.

The Conditioning Trap: Why Self-Criticism Feels “Normal”

If self-compassion feels unnatural or you grew up believing being hard on yourself was the key to success, you’re not alone. Many of us were raised on a steady diet of conditional love and motivational shame—the idea that if we punish ourselves enough, we’ll finally improve.

Most of us inherited invisible scripts:

“Don’t be selfish.”

“Push harder.”

“You can rest when you’re done.”

“Good people put others first.”

From early school grading systems to workplace performance reviews, we’re trained to value achievement over well-being, we’re rewarded for self-control but rarely taught self-kindness. Many clients—especially women, caregivers, and high achievers—internalize a false dichotomy: that being compassionate to yourself is indulgent, while being hard on yourself is virtuous. Society tells them self-sacrifice is saintly, while self-kindness is selfish.

But here’s the twist: neuroscience shows self-criticism doesn’t motivate us—it immobilizes us. Chronic self-criticism activates the same neural networks as being attacked by another person (Gilbert & Procter, 2006). The body doesn’t distinguish between external and internal hostility—It simply floods the body with cortisol, reduces memory and immune function, and keeps the nervous system locked in threat mode [5]. Over time, this internalized attack loop can turns your inner dialogue into a hostile workplace filled with burnout, anxiety, depression, and relational strain.

In contrast, self-compassion activates the brain’s care system, releasing oxytocin and dopamine—the same chemicals responsible for connection and trust [6]. People high in self-compassion actually show greater accountability and persistence after failure [7]. In one study, those who responded kindly to mistakes were more likely to take corrective action instead of spiraling into guilt [8].

Research even debunks the productivity myth: people high in self-compassion persist longer after setbacks, take greater responsibility for mistakes, and show more intrinsic motivation (Breines & Chen, 2012; Magnus et al., 2010). Being kind to yourself isn’t laziness—it’s psychological efficiency.

Dr. Paul Gilbert’s Compassion-Focused Therapy model explains that humans have three primary affect-regulation systems: threat, drive, and soothing. Most people in modern society live between threat (“I’m not enough”) and drive (“I’ll prove I’m enough”), rarely accessing soothing (“I am safe enough”). Self-compassion is the only practice that activates the soothing system, restoring physiological balance.

So if you’ve been raised to believe compassion makes you weak and soft, consider this: nature literally designed your body to heal through warmth, not war.

The Bootcamp Myth: When Healing Becomes Self-Punishment

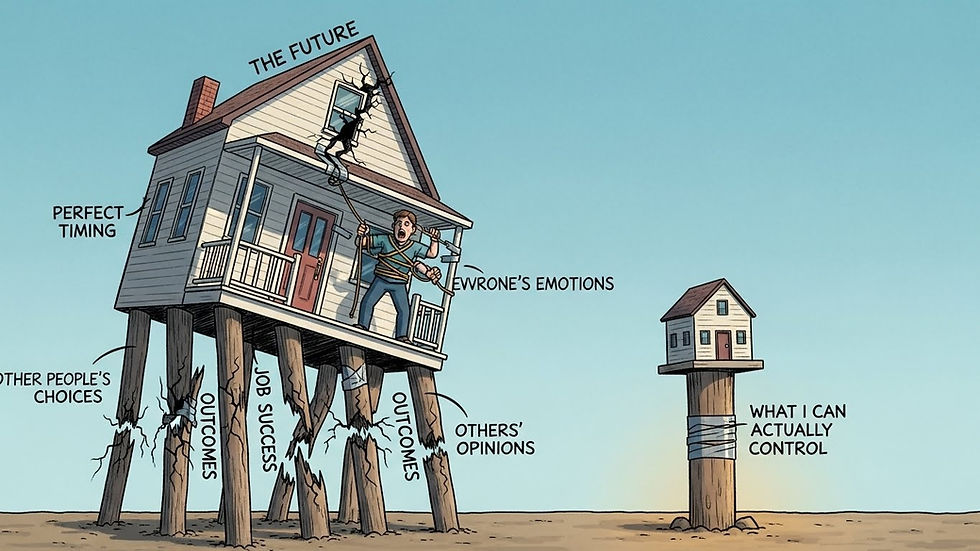

Here’s the paradox: the harder you try to force healing, the slower it goes. Nowhere does this conditioning show up more clearly than in the therapy room. I’ve watched countless clients turn healing into another competition: “If I work hard enough, meditate long enough, or journal every day, I’ll finally be fixed.” They treated therapy like a fitness challenge—setting emotional PRs, tracking progress, and berating themselves for “missing reps.”

The problem? That mindset assumes you’re broken. It turns therapy into a performance of worthiness rather than a process of integration. The harder people pushed, the more frustrated they became when “progress” didn’t look linear. Sessions became checklists, not connections. Self-criticism kept the nervous system in a constant state of defense. You can’t rewire your brain when it thinks you’re under siege. Healing can’t happen in a nervous system that believes it’s under attack—even when the attacker is you.

But self-criticism doesn’t accelerate change—it paralyzes it. Studies show that self-critical individuals have lower heart-rate variability, weaker immune function, and slower recovery from emotional stress (Longe et al., 2010; Rockliff et al., 2008). Their brains literally stay locked in the “unsafe” position.

The paradox of healing is this: you can’t bully your way to wholeness. Every moment of impatience, every “I should be further along,” every inner reprimand is a signal to your body that you’re not safe enough to relax into transformation.

Research shows that people who respond to setbacks with compassion recover faster, experience lower stress reactivity, and demonstrate higher cognitive flexibility [9]. Healing isn’t a war to win—it’s a relationship to nurture. You can’t build emotional safety by yelling at yourself to calm down. You can’t rewire a threat-based brain with more threat. And yet, so many people live in this loop: criticize, collapse, repeat.

The way out? Stop managing yourself like an employee who’s underperforming and start caring for yourself like someone you actually want to see thrive.

Self-compassion doesn’t mean you stop growing—it means you finally stop growing out of fear.

The Rewiring Protocol: Building a Compassionate Brain

Your brain is not fixed—it’s rewritable. Through neuroplasticity, every compassionate thought literally lays new neural tracks that make self-kindness more automatic over time (Longe et al., 2010). Below are evidence-based practices, drawn from research and from The Self-Compassion Development Guide, that reprogram the nervous system from self-attack to self-support.

✳️ For a full practice guide, download your free resource: The Self-Compassion Development Guide.

Below are evidence-based tools that train your brain for kindness—and why each works.

1. The Self-Compassion Break (Neff, 2011)

This 60-second practice interrupts self-criticism mid-spiral. You pause, name your suffering (“This is hard”), remind yourself you’re not alone (“Everyone struggles”), and offer kindness (“May I be gentle with myself”).

Why it works: It activates the brain’s soothing system while inhibiting the threat system, lowering cortisol levels and shifting emotional regulation from reactivity to resilience [12]. Regular practice has been linked to reduced anxiety and increased heart rate variability—a marker of emotional flexibility.

A 3-step micro-practice to calm the body’s threat response in real time:

Mindfulness: “This is a moment of suffering.”

Common Humanity: “I’m not alone; everyone struggles.”

Self-Kindness: “May I be kind to myself right now.” Practicing even one minute daily lowers physiological stress markers.

2. Compassionate Self-Talk

When your inner critic starts ranting, reframe the message. Replace, “What’s wrong with me?” with “This is tough—and I’m doing my best.”

Why it works: Your brain believes the tone of your inner voice as if it were coming from another person. Studies show that self-reassurance increases activation in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, associated with emotional safety [13]. You’re essentially becoming your own secure attachment figure.

Self-critical: “I should be over this by now.”

Compassionate: “It makes sense this still hurts; I’m learning to heal.” This practice retrains the default internal dialogue that shapes self-concept (Neff, 2011; Critcher & Dunning, 2015).

3. Somatic Compassion Practice

Self-compassion isn’t only cognitive—it’s embodied. Place a hand over your heart or another soothing area when stressed, breathe slowly, and silently repeat, “I care about this pain.”

Why it works: Physical touch triggers oxytocin release, signaling safety to the nervous system [14]. It’s the same system activated when a loved one comforts you. Over time, your body learns to associate your own touch with calm instead of crisis.

4. Compassionate Parts Dialogue (IFS-Inspired)

When shame arises, instead of suppressing it, acknowledge it as a protective part. Ask: "What are you trying to protect me from?"

Why it works: This approach, grounded in Internal Family Systems therapy [15], integrates exiled self-parts rather than rejecting them. fMRI research shows this reduces activation in the amygdala and increases prefrontal integration—basically helping your brain process old pain without re-traumatization.

When shame surfaces:

Identify: “A part of me feels ashamed about…”

Ask: “What is this part protecting me from?”

Acknowledge: “Thank you for trying to keep me safe.” This integrates exiled self-parts rather than rejecting them, promoting emotional wholeness (Schwartz, 2021).

5. The Self-Compassion Letter

Write a letter to yourself from the perspective of an unconditionally loving friend. Acknowledge pain, affirm worth, and remind yourself that imperfection is not failure—it’s humanity. Research shows expressive writing combined with compassion increases resilience and cognitive flexibility (Howell et al., 2016).

Why it works: Expressive writing with compassion enhances emotional processing and self-acceptance [16]. It increases activity in brain regions related to empathy and cognitive reappraisal—which means you’re literally teaching your brain to interpret pain differently.

6. The Common Humanity Reflection

When shame whispers, “You’re the only one,” pause and remember: pain is the most universal human language. Reflect on how many others have faced something similar.

Why it works: This breaks isolation—a core fuel for shame. Dr. Neff’s research shows that people who recognize their struggles as common experience less emotional distress and recover from setbacks faster [17].

When judgment arises, pause and ask:

How many people have felt this too?

What would I say to them if they were in my place? This exercise dissolves isolation—the fertile soil of shame (Brown, 2012).

7. The Compassionate Boundary Reset

Compassion doesn’t mean permissiveness. Before setting a boundary, affirm:“Protecting my peace isn’t selfish—it’s responsible.” Boundaries are compassion in action.

Why it works: Healthy boundaries signal to your nervous system that you can meet your own needs safely. This enhances self-trust, a key predictor of emotional regulation and reduced burnout [18].

8. Integration Protocol: Morning-to-Evening Compassion Habits

Start small. Morning: set an intention to treat yourself kindly. Midday: one mindful breath and hand-on-heart check-in. Evening: recall one moment you offered yourself grace.

Why it works: Repetition builds default pathways. Consistent micro-moments of compassion condition your brain to expect safety, reducing baseline anxiety and improving sleep quality [19].

Morning intention: “May I treat myself with the same kindness I offer others.”

Midday check-in: One mindful breath and hand-on-heart moment.

Evening reflection: Identify one act of self-kindness from the day.

Small, frequent compassionate acts accumulate faster neural change than occasional deep dives.

The Ripple Effect: Compassion Transforms Everything

Self-compassion isn’t just an internal balm—it reshapes how you show up in the world. It doesn’t just make you feel better—it makes you be better. Research demonstrates that people high in self-compassion experience stronger relationships, better emotion regulation, and higher empathy (Neff, 2011; Germer, 2009). In couples therapy, it predicts reduced defensiveness and greater conflict resolution. In professional settings, it correlates with innovation, creativity, leadership resilience, and ethical decision-making.

And here’s the kicker: compassion for self expands compassion for others. Compassion becomes a quiet revolution. When you no longer demand perfection from yourself, you stop demanding it from others. Once your inner critic retires, you stop needing to project it onto everyone else. Intimacy deepens. Creativity expands. The nervous system learns that it’s safe not just to survive—but to connect.

Self-compassion is not self-centered. It’s self-sustaining. When you stop treating kindness as a reward for performance, it becomes the energy source for growth.

The Real Work: From Fixing to Befriending

The irony of healing is that it begins the moment you stop trying to fix yourself and trying to earn your own worth. You were never broken—only disconnected from the parts that needed your gentleness and kindness the most.

Every time you choose understanding over judgment, you’re not letting yourself off the hook—you’re reprogramming the brain’s threat response into safety, trust, and integration.

Self-compassion isn’t a detour from healing—it is the road.

References

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(2), 107–118.

Breines, J. G., & Chen, S. (2012). Self-compassion increases self-improvement motivation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(9), 1133–1143.

Brown, B. (2012). Daring Greatly. Gotham.

Critcher, C. R., & Dunning, D. (2015). Self-affirmations provide a broader perspective on self-threat. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(1), 3–18.

Davidson, R. J., & McEwen, B. S. (2012). Social influences on neuroplasticity: Stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nature Neuroscience, 15(5), 689–695.

Gilbert, P., & Procter, S. (2006). Compassionate mind training for people with high shame and self-criticism. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 13(6), 353–379.

Germer, C. K. (2009). The Mindful Path to Self-Compassion. Guilford Press.

Howell, A. J., et al. (2016). The disposition to apologize. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 178–184.

Kim, J. J., et al. (2020). Neural and psychological mechanisms of self-reassurance versus self-criticism. Human Brain Mapping, 41(7), 1955–1968.

Kirsch, P., et al. (2005). Oxytocin modulates neural circuitry for social cognition and fear. Journal of Neuroscience, 25(49), 11489–11493.

Leary, M. R., et al. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904.

Longe, O., et al. (2010). Neural correlates of self-criticism and self-reassurance. NeuroImage, 49(2), 1849–1856.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32(6), 545–552.

Magnus, C. M., et al. (2010). The role of self-compassion in women’s self-determined motives to exercise. Self and Identity, 9(4), 363–382.

Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow.

Neff, K. D., & Dahm, K. A. (2015). Self-compassion: What it is, what it does, and how it relates to mindfulness. In Handbook of Mindfulness and Self-Regulation. Springer.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28–44.

Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2017). Self-compassion and psychological well-being. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1388–1395.

Rockliff, H., et al. (2008). Heart rate variability and cortisol responses to compassion-focused imagery. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 5(3), 132–139.

Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No Bad Parts. Sounds True.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The Developing Mind. Guilford Press.

Uvnäs-Moberg, K. (2009). The Oxytocin Factor. Perseus Publishing.

Vettese, L. C., et al. (2011). Does self-compassion mitigate the effects of childhood maltreatment? Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(2), 126–135.

Zessin, U., et al. (2015). Self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7(3), 340–364.

Comments