The Invisible Wounds: Why Your "Normal" Childhood Might Be the Real Reason You Can't Feel Good Enough (And It's Not Your Fault)

- Natasha Bussey

- Aug 20, 2025

- 10 min read

"The greatest tragedy is not the abuse or neglect you suffered, but that you learned to call it love." —Dr. Gabor Maté.

Here's a question that might make you uncomfortable: What if I told you that trauma isn't just war veterans and abuse survivors? What if the reason you constantly feel "not quite enough," struggle with perfectionism, or find yourself people-pleasing until you're exhausted has nothing to do with your character flaws and everything to do with invisible wounds that accumulated so gradually you never noticed them forming?

Welcome to the revolutionary world of microtrauma—where science is discovering that the most damaging psychological injuries often come not from single catastrophic events, but from thousands of tiny moments when you learned that your authentic self wasn't acceptable, your feelings didn't matter, or your worth was conditional on performance.

This isn't about blame or victimhood. This is about understanding why so many "successful" people from "good families" still feel fundamentally broken inside—and more importantly, how to heal wounds you didn't even know you had.

The Microtrauma Revolution: Redefining What Actually Hurts Us

Let's start by exploding a myth that's causing massive psychological damage: the idea that trauma requires dramatic, obvious events. Dr. Gabor Maté's groundbreaking research reveals that what he calls "small-t trauma" (microtrauma) is actually more prevalent and often more psychologically damaging than "big-T trauma" (major traumatic events) [1].

Here's why this matters: Dr. Bessel van der Kolk's research shows that while 70% of adults have experienced at least one traumatic event, over 90% have experienced multiple microtraumas that shape their nervous systems and self-concept in profound ways [2]. The brain doesn't distinguish between a single large wound and thousands of tiny cuts—the cumulative damage is often identical.

Dr. Alice Miller's pioneering research on childhood emotional neglect found that children who grew up in "perfectly normal" families often show the same psychological patterns as those who experienced obvious abuse: chronic self-doubt, emotional dysregulation, and what she calls "the drama of the gifted child"—high achievement coupled with deep insecurity [3].

Brain imaging studies by Dr. Allan Schore reveal that microtraumas actually create more complex psychological patterns than single-event traumas because they become woven into identity formation during critical developmental periods [4]. Your brain didn't just experience these wounds—it organized itself around them.

The Anatomy of Invisible Wounds: How "Good Enough" Parenting Creates Not-Good-Enough Adults

Here's what might surprise you: most microtrauma doesn't come from "bad" parents. It comes from well-meaning caregivers who simply weren't equipped to handle the full emotional reality of raising humans. Dr. Diana Baumrind's research on parenting styles shows that even "authoritative" (considered ideal) parenting can create microtrauma when it prioritizes compliance over authentic emotional expression [5].

The Top 5 Microtrauma Patterns from "Normal" Childhoods:

1. Emotional Invalidation

Research by Dr. Marsha Linehan shows that phrases like "You're too sensitive," "Don't cry," or "There's nothing to be afraid of" teach children that their emotional reality is fundamentally wrong [6].

The child's brain learns: My feelings are unacceptable.

2. Conditional Love Performance

Dr. Carl Rogers' research reveals that praise tied to achievement ("I'm so proud when you get good grades") creates what he calls "conditions of worth"—the belief that love must be earned through performance [7].

The brain learns: I am only valuable when I achieve.

3. Comparison and Competition

Studies by Dr. Leon Festinger show that children constantly compared to siblings or peers develop chronic social comparison habits and never-enough feelings [8].

The brain learns: I am only as good as I am better than others.

4. Emotional Parentification

Research by Dr. Gregory Jurkovic found that children who become their parents' emotional support system (listening to marital problems, managing parental emotions) develop hypervigilance and boundary issues [9].

The brain learns: My needs don't matter; I exist to take care of others.

5. Perfectionism Training

Dr. Brené Brown's research shows that children who receive the message that mistakes are unacceptable develop what she calls "shame resilience deficits" [10].

The brain learns: Any imperfection makes me fundamentally flawed.

The Nervous System Never Forgets: How Microtrauma Lives in Your Body

Here's where the science gets fascinating and disturbing: Dr. Stephen Porges' Polyvagal Theory reveals that microtrauma doesn't just create psychological patterns—it literally shapes your autonomic nervous system [11]. Children who experience chronic invalidation, comparison, or conditional love develop what researchers call "complex trauma responses":

Hypervigilance: Constantly scanning for approval/disapproval

Emotional dysregulation: Big reactions to small triggers

Chronic shame: Deep sense of being fundamentally flawed

People-pleasing: Compulsive need to avoid conflict or rejection

Perfectionism: Terror of making mistakes or being "found out"

Imposter syndrome: Feeling like a fraud despite evidence of competence [12]

Dr. Gabor Maté's research shows that adults with microtrauma histories have measurably different stress hormone patterns, inflammation markers, and even gene expression compared to those who experienced consistent emotional attunement in childhood [13]. Your body is still responding to threats that happened decades ago.

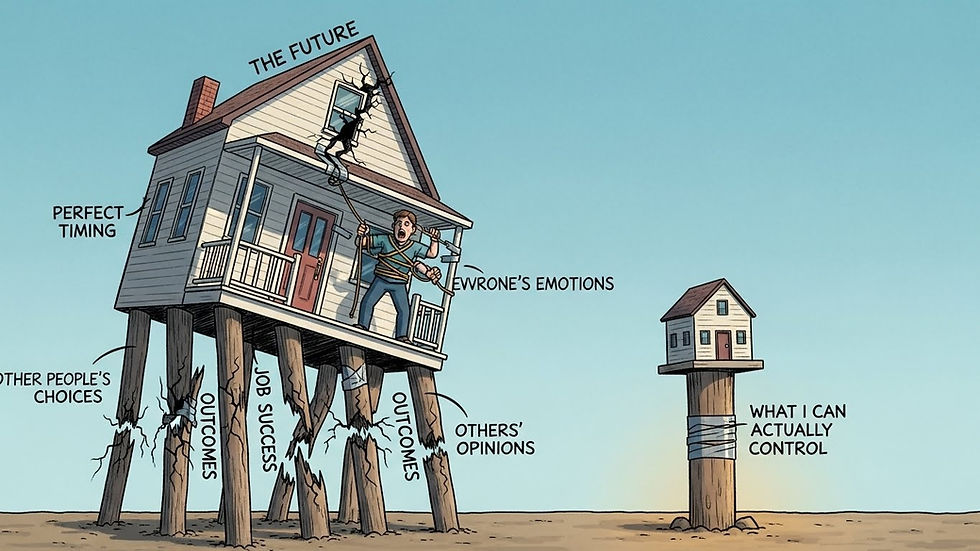

The Comparison Trap: How "Everyone Else Had It Worse" Keeps You Stuck

One of the most damaging aspects of microtrauma is what Dr. Pete Walker calls "emotional neglect minimization" [14]. Because your wounds aren't dramatic, you dismiss them. Because your parents "did their best," you feel guilty for being hurt. Because others "had it worse," you feel like your pain doesn't count.

Research by Dr. Jonice Webb reveals this is exactly backward: the invisibility of emotional neglect makes it more damaging, not less [15]. When abuse is obvious, at least you know something happened to you. When microtrauma is subtle, you grow up thinking you're just naturally broken.

Dr. Lindsay Gibson's research on "emotionally immature parents" found that children who can't point to specific abuse often struggle more with healing because they have no clear target for their pain [16]. They just know something feels fundamentally wrong with them.

Studies show that microtrauma survivors often exhibit what researchers call "impaired self-compassion"—they can feel empathy for others who experienced similar situations but remain harshly critical of their own experience [17]. You'd never tell a friend their childhood emotional neglect "wasn't that bad," but you tell yourself that daily.

The Healing Paradox: Why Traditional Therapy Sometimes Misses the Mark

Here's a controversial truth: traditional talk therapy often fails microtrauma survivors because it's designed for discrete events, not chronic patterns. Dr. Judith Herman's research shows that complex trauma requires different therapeutic approaches than single-incident trauma [18].

Standard therapy assumes you can identify what happened and process it. But how do you process the thousand moments when your emotions were dismissed? How do you heal from what didn't happen (emotional attunement) rather than what did happen (abuse)?

Dr. Richard Schwartz's Internal Family Systems research reveals that microtrauma survivors often have what he calls "exiled parts"—aspects of themselves they learned to hide or suppress [19]. Healing requires not just processing memories, but reclaiming disowned parts of your authentic self.

The Microtrauma Recovery Roadmap: Healing Wounds You Can't See

Phase 1: Recognition Without Minimization (Weeks 1-4)

The Validation Practice: Research by Dr. Kristin Neff shows that self-compassion practices specifically counteract the minimization patterns common in microtrauma [20].

Daily Practice: Each evening, complete this sentence: "It makes sense that I feel _____ because my younger self needed _____ and didn't receive it."

The Emotional Archaeology Exercise: Dr. Alice Miller's research suggests that buried childhood emotions often emerge through present-day triggers [21].

Weekly Practice: When you have strong emotional reactions, ask: "How old do I feel right now? What did that younger version of me need in this moment?"

Phase 2: Nervous System Regulation (Weeks 5-8)

The Safety Signal Practice: Dr. Deb Dana's research on Polyvagal Theory shows that microtrauma survivors need to actively teach their nervous systems that they're safe now [22].

Daily Practice: Three times daily, place hand on heart and say: "I am safe now. I am allowed to feel. My emotions are valid."

The Boundary Building Protocol: Research by Dr. Henry Cloud shows that microtrauma survivors often have impaired boundary development [23].

Weekly Practice: Practice saying "no" to one small request without explanation or justification. Notice the physical sensations and emotional reactions.

Phase 3: Authentic Self Reclamation (Weeks 9-12)

The Part Retrieval Exercise: Dr. Richard Schwartz's research shows that healing involves welcoming back exiled aspects of self [24].

Monthly Practice: Write a letter to your younger self acknowledging the parts you had to hide: "I see you, playful child. I see you, sensitive soul. I see you, angry protector. You are welcome here now."

The Unconditional Self-Worth Practice: Dr. Carl Rogers' research on unconditional positive regard shows this must be developed internally when it wasn't received externally [25].

Daily Practice: Each morning, look in mirror and say: "I love and accept you exactly as you are right now, not for what you accomplish or how you perform."

The Reparenting Revolution: Becoming the Parent You Needed

Dr. Alice Miller's research reveals a profound truth: healing microtrauma often requires "reparenting" yourself—providing the emotional attunement you needed but didn't receive [26]. This isn't about blaming your parents; it's about taking responsibility for giving yourself what you still need.

The Inner Child Integration Protocol (based on Dr. John Bradshaw's research [27]):

Morning Check-ins: "How are you feeling today, little one?"

Emotional Validation: "It's okay to feel scared/sad/angry"

Unconditional Presence: "I'm here with you no matter what"

Protective Boundaries: "I won't let anyone treat you badly"

Celebratory Moments: "I'm proud of you just for being you"

Research shows that adults who practice consistent self-reparenting show measurable improvements in self-esteem, emotional regulation, and relationship satisfaction within 12 weeks [28].

The Integration Challenge: Healing Without Losing Yourself

One of the biggest fears microtrauma survivors have about healing is: "If I change these patterns, will I still be me?" Dr. Dan Siegel's research on neuroplasticity reveals that healing doesn't erase your personality—it reveals your authentic self beneath the protective adaptations [29].

The perfectionism that exhausts you? Underneath is a beautiful attention to detail and care for quality.

The people-pleasing that drains you? Underneath is genuine empathy and desire to help.

The hypervigilance that stresses you? Underneath is sophisticated emotional intelligence and awareness.

Healing microtrauma isn't about becoming someone different—it's about becoming who you actually are when you're not constantly defending against old wounds.

The Objection-Crusher Section

"But my parents did their best with what they had."

Absolutely true, and this doesn't negate the impact on you. Dr. Gabor Maté's research shows that understanding your parents' limitations helps with forgiveness but doesn't heal your nervous system [30]. Both can be true: they did their best AND you were hurt.

"Other people had it so much worse."

Pain isn't a competition. Research by Dr. Jonice Webb shows that emotional neglect can be as damaging as overt abuse, just harder to identify [31]. Your wounds don't need to be the worst to deserve healing.

"I turned out fine—I'm successful."

External success often masks internal struggles. Dr. Alice Miller's research on "the drama of the gifted child" shows that high achievers frequently have the deepest microtrauma wounds [32]. Success despite wounds doesn't mean the wounds don't need healing.

"I don't want to dwell on the past."

Healing isn't dwelling—it's liberating. Dr. Bessel van der Kolk's research shows that unprocessed microtrauma continues affecting you unconsciously [33]. Conscious healing stops the past from unconsciously controlling your present.

Your Healing Journey Starts with One Truth

Here's what I need you to understand: you're not broken, dramatic, or "too sensitive." You're a human being whose emotional development was interrupted by well-meaning people who didn't know how to handle the full complexity of feelings. Your struggles with self-worth, perfectionism, or feeling "never enough" aren't character flaws—they're adaptive responses to an environment that couldn't fully see and accept you.

The little person inside you who learned to hide their true feelings, perform for love, and constantly compare themselves to others is still there, waiting for someone to finally say: "I see you. I believe you. Your feelings matter. You are enough exactly as you are."

That someone is you. Today can be the day you stop minimizing your invisible wounds and start the radical act of emotional self-rescue.

Your younger self has been waiting long enough. They deserve a champion, a protector, a loving parent who never leaves. They deserve you, showing up with all the emotional attunement they needed then and still need now.

The healing begins the moment you stop saying "it wasn't that bad" and start saying "it was bad enough to hurt me, and that matters."

What would change if you truly believed your pain counts?

References:

1. Maté, G., & Maté, D. (2022). The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture. Avery.

2. van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

3. Miller, A. (2008). The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self. Basic Books.

4. Schore, A. N. (2019). The Development of the Unconscious Mind. Norton.

5. Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11(1), 56-95.

6. Linehan, M. M. (2014). DBT Skills Training Manual. Guilford Publications.

7. Rogers, C. R. (1961). On Becoming a Person: A Therapist's View of Psychotherapy. Houghton Mifflin.

8. Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117-140.

9. Jurkovic, G. J. (1997). Lost Childhoods: The Plight of the Parentified Child. Brunner/Mazel.

10. Brown, B. (2010). The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. Hazelden.

11. Porges, S. W. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-regulation. Norton.

12. Ford, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2020). Treating Complex Traumatic Stress Disorders in Adults. Guilford Press.

13. Maté, G. (2003). When the Body Says No: Exploring the Stress-Disease Connection. Wiley.

14. Walker, P. (2013). Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving. Azure Coyote.

15. Webb, J. (2012). Running on Empty: Overcome Your Childhood Emotional Neglect. Morgan James Publishing.

16. Gibson, L. C. (2015). Adult Children of Emotionally Immature Parents. New Harbinger.

17. Neff, K. D. (2011). Self-Compassion: The Proven Power of Being Kind to Yourself. William Morrow.

18. Herman, J. L. (2015). Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence. Basic Books.

19. Schwartz, R. C. (2021). No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model. Sounds True.

20. Neff, K. D., & Germer, C. K. (2013). A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(1), 28-44.

21. Miller, A. (2005). The Body Never Lies: The Lingering Effects of Hurtful Parenting. Norton.

22. Dana, D. (2018). The Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Engaging the Rhythm of Regulation. Norton.

23. Cloud, H., & Townsend, J. (2017). Boundaries: When to Say Yes, How to Say No to Take Control of Your Life. Zondervan.

24. Schwartz, R. C. (2001). Introduction to the Internal Family Systems. Trailheads Publications.

25. Rogers, C. R. (1957). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(2), 95-103.

26. Miller, A. (1997). The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self. Basic Books.

27. Bradshaw, J. (2005). Homecoming: Reclaiming and Healing Your Inner Child. Bantam.

28. Whitfield, C. L. (2013). Healing the Child Within: Discovery and Recovery for Adult Children of Dysfunctional Families. Health Communications.

29. Siegel, D. J. (2020). The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. Guilford Press.

30. Maté, G. (2008). In the Realm of Hungry Ghosts: Close Encounters with Addiction. North Atlantic Books.

31. Webb, J., & Bell, C. (2012). Running on Empty: Overcome Your Childhood Emotional Neglect. Morgan James Publishing.

32. Miller, A. (2008). The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self. Basic Books.

33. van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Viking.

Comments